..............................................................................................................................................................

..............................................................................................................................................................

Reentry Of Spaceships

What Keeps Spaceships from Burning Up During

Reentry?

Written by Maverick Baker

By Interesting Engineering

Thanks to engineers and scientists, it is now possible to

survive a fall while burning up at thousands of degrees during atmospheric

reentry.

Getting astronauts into space challenges engineers

with unprecedentedly difficult problems.

Though the spacecraft may have been proven during the

launch and duration of space exposure, it must still endure one of the most

demanding challenges of all: reentry.

At the end of a mission, spaceships re-enter the

Earth's atmosphere as they travel in excess of 30,000 km/h.

The tremendous speed of the reentry vehicle compresses

the air below into a hot ball of plasma which encircles the craft.

Getting the astronauts home safely will require

protecting them from the heat as it reaches thousands of degrees.

The dangers of reentry

Archeologists have long understood that asteroids burn

up as they fall through the atmosphere.

The fact instilled fear into scientists for decades as

they wondered about the possibility of engineering a vehicle strong enough to

withstand the perilous environment that reentry creates.

One of the greatest challenges imposed on aerospace

engineers is developing a thermal protective material which does not become

compromised, even at temperatures as high as 1,700-degrees Celsius.

A variety of Thermal Protection Systems (TPS) is

employed to prevent spaceships from preemptively burning. The heat shield is a

reentry vehicle's primary defense against the intense heat experienced as they

fall through the atmosphere.

Disaster strikes

One of the hard-learned lessons of reentry was during

Columbia's fatal flight on Feb. 1, 2003.

During the launch, a large piece of foam about the

size of a briefcase, tore loose and caused some damage to a heat shield panel

on the left wing.

The mission proceeded as usual until disaster struck

during reentry. Superheated plasma penetrated the compromised wing and quickly

burnt its structure.

Unfortunately, the Columbia began an uncontrollable

tumble, causing it to disintegrate. Seven astronauts lost their lives that day.

However, the unfortunate accident would force NASA to

redesign the Space Shuttle. More than a decade later, NASA is implementing the

lessons learned on its new ship, Orion.

Previous technologies

Early manned spacecraft including Mercury, Gemini, and

Apollo, could not be maneuvered during reentry.

The space capsules had followed ballistic re-entry

trajectories before they plummeted into the ocean.

Large heat-shields constructed of phenolic epoxy

resins in a nickel-alloy honeycomb array protected the capsules during reentry.

The shields could withstand incredibly high heating rates, a dire necessity

among reentry vehicles.

The Apollo moon missions posed a great engineering

hurdle since the capsules, as they returned from the moon and enter the

atmosphere at more than 40,000 km/h.

The heat shield was able to ablate or burn the char

layer controllably to protect the underlying layers. Though the heat shield was

effective, there were some critical drawbacks.

The shields were heavy and were bound directly to the

vehicle. Moreover, they were not reusable.

Perhaps the most impressive thermal protection system

(TPS) belongs to that of the Space Shuttle orbiter. The Space Shuttle program

required an entirely redesigned heat shield.

With an incredibly long design life of 100 missions,

its insulation not only had to perform well but also needed to be reusable. Its

engineering success will provide the innovative technologies which will carry

into the next generation of space programs.

The Space Shuttle thermal protection system

In space, the Orbiter would circle the world every

90-minutes. The time from day to night would see temperature fluctuations of

-130 degrees Celsius to nearly 100-degrees Celsius, let alone the temperatures

of reentry.

Though there exist many materials which are durable

enough to withstand the forces of reentry, not many can withstand the heat.

During reentry of the Orbiter, its external surfaces reached extreme

temperatures of up to 1,648°C (3,000°F).

Despite the extreme heat experienced by the TPS, many

systems work together to maintain the Orbiter's outer skin at under 176°C

(350°F).

Although the external components may be able to

survive hundreds of degrees, the aluminum airframe can only withstand

temperatures of up to a maximum of 150°C.

Temperatures much beyond the threshold will cause the

frame to become soft and compromised as a result. The thermal protection

systems in place ensure the airframe does not exceed the thermal limit.

The materials used to keep the Orbiter cool

NASA's first operational orbiter, otherwise known as

the Columbia, was constructed from four primary materials.

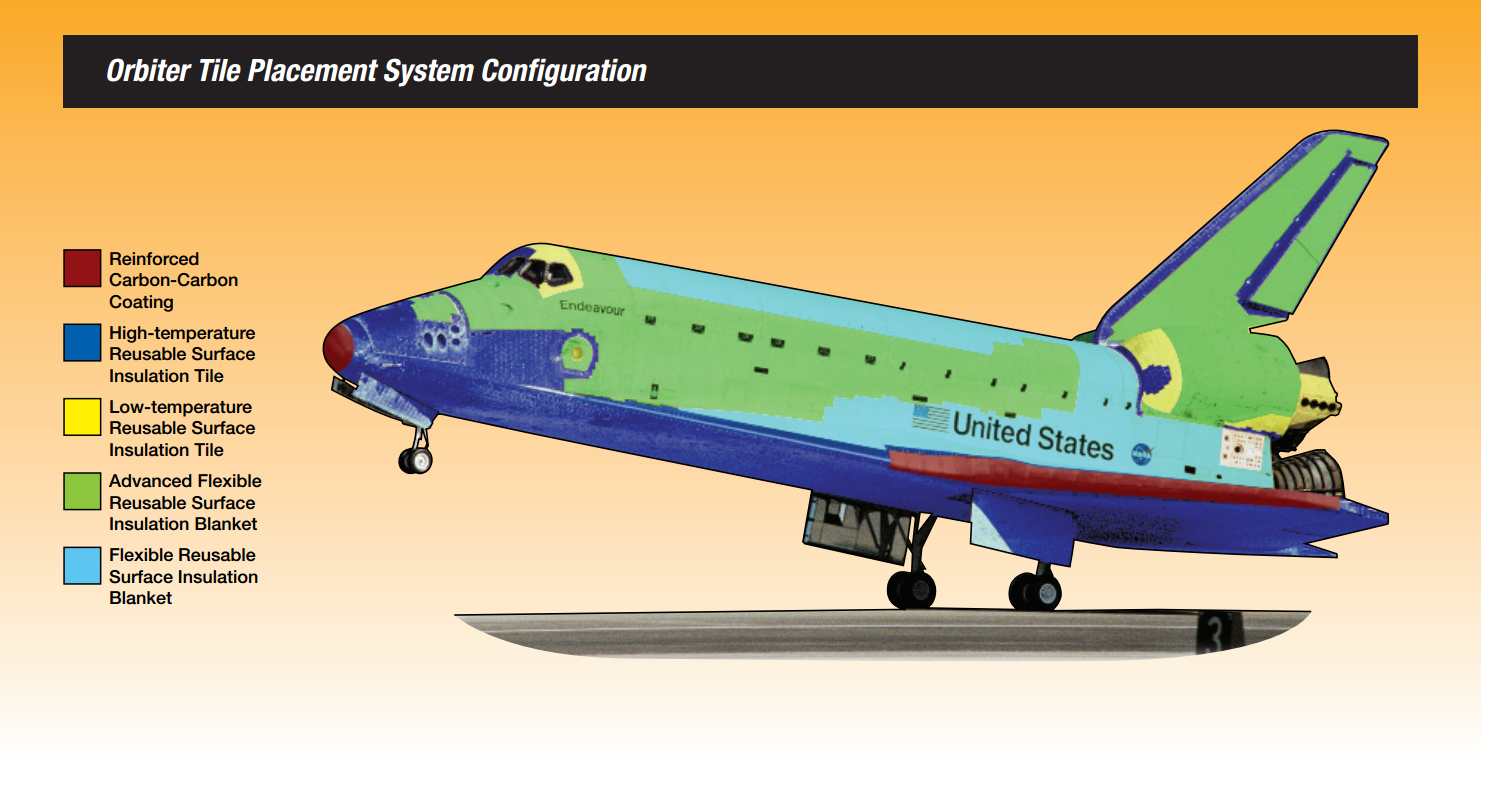

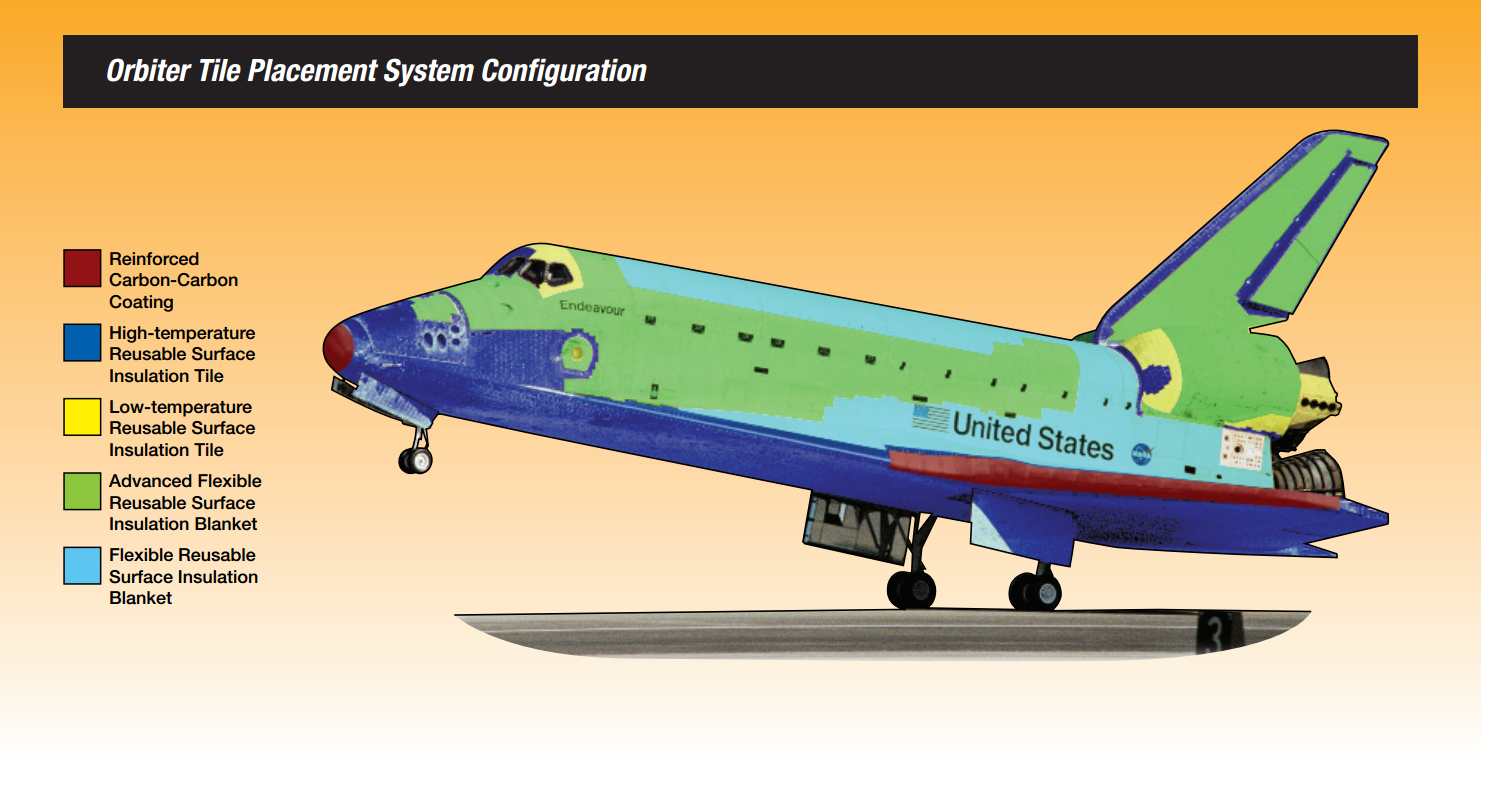

The materials include reinforced carbon-carbon (RCC),

low- and high-temperature reusable surface insulation tiles (LRSI and HRSI,

respectively), and felt reusable surface insulation (FRSI) blankets.

Different parts of the aircraft experience different

temperatures and therefore require different materials.

The parts most exposed to heat, including the nose and

underside of the Orbiter, are made from the most thermally resistant materials.

The leading edges require an additionally reinforced

carbon-carbon coating on top of the high-temperature insulation tiles.

Other areas, including most of the fuselage, were

covered in advanced flexible and reusable insulation blankets.

All components which come into contact with the

outside are covered in high emissivity coatings to ensure the Shuttle reflects

off most of the thermal heat. Though, the difference in color plays a vital role

as well.

Black and white tiles, while similar in composition,

perform different tasks during reentry.

The white tiles on the upper surface of the material

retain a high thermal reflectivity (a tendency to absorb minimal heat). The

black tiles are instead optimized for maximum emissivity which allows them to

lose heat faster than white tiles.

How they work

The tiles which take much of the brute force during

reentry are made of silica aerogels. The material used on the underside of the

Orbiter (known as LI-900) is 94 percent by volume of air making it incredibly

light.

The tiles are specifically designed to withstand

thermal shock. An LI-900 is capable of being heated to 1200 degrees then take a

plunge into cold water without sustaining damage.

Though, optimizing the tiles with a low density and

high shock resistance lead to a compromise in its overall strength.

Areas of high stress require a more robust material; a

problem later solved by the material LI-2200. LI-2200 tiles are modified to

withstand more force. Though, the stronger tiles have their drawbacks as well.

An LI-2200 tile weighs 22 pounds per cubic foot bulk

density compared to the much lighter LI-900 with a density of just 9 pounds per

cubic foot.

Re-entering the atmosphere today

Though astronauts have not visited the moon in a

while, and though the space shuttle program has since been abandoned,

astronauts routinely visit the ISS to perform experiments and repairs.

Though the spaceships have changed, the technologies

which bring them back home retain the same principles.

Orion Spacecraft

NASA's current magnum opus is their revolutionary

Orion spacecraft.

NASA promises the spacecraft will take humans farther

than ever before, including Mars. Although, the new spacecraft required a total

overhaul of its reentry systems.

While the Space Shuttle has remarkable TPS, engineers

have largely abandoned the idea of reusable thermal shields in favor of cheap,

easily manufactured single-use tiles.

The Orion capsule will not glide in as the Space

Shuttle once did. Instead, parachutes are used to ensure a safe return to

Earth. Orion's crew module is designed to reenter at speeds of more than 40,000

km/h.

How the Orion survives reentry

The large surface area of the bottom of the capsule

works to take the blunt of the force. Like the Apollo reentry vehicles, Orion's

heat shield is engineered to ablate (controllable burn).

The shield is aerodynamic enough to maintain a stable

flight path, yet blunt enough to slow the descent to a speed of just 500 km/h.

How to Land A Space Shuttle

After achieving a reasonable rate, several small

parachutes just over 2 meters in diameter slow the aircraft by only 30

km/h.

From there, a series of large parachutes with

diameters of 7-metres are deployed to slow the capsule to 200 km/h just

3-kilometers above the surface of the Earth.

Finally, three massive main parachutes with a diameter

of 35 meters each slow the rate of descent to a survivable speed. Though the

landing is not pretty.

However, it is through the hard daunting work

astronauts perform today that will advance humanity to make the next giant

leap.

Soon, missions will take humans far beyond the reach

of the Earth to explore otherworldly planets.

Founded on the core mission of connecting

likeminded engineers around the globe, Interesting Engineering is now a

leading community with more than 15 million+ minds. Every day we share a new

idea, a new thought, an upcoming technology OR an engineering breakthrough that

will change the way you think about technology and engineering in today’s world

and in the near future. Whether it’s a device that can charge your mobile in

seconds or it’s the latest model of Boeing that has launched moments ago, we

will bring everything up on your screen to view, to share and to grant you the

power to comment. We believe that sharing information is the only way that can

enrich and empower humans on this earth and we follow this as our core mission

and responsibility. If you have got something that could entice the world, then

Interesting Engineering is a perfect platform to show off your work to the

outside world.

No comments:

Post a Comment