...................................................................................................................................................................

Large-scale Water Supply

The Open University

The need for large-scale water treatment

Water treatment is the process of removing all

those substances, whether biological, chemical or physical, that are

potentially harmful in water supply for human and domestic use.

This treatment helps to produce water that is

safe, palatable, clear, colourless and odourless. Water also needs to be

non-corrosive, meaning it will not cause damage to pipework.

In urban areas, many people live close together

and they all need water. This creates a demand for large volumes of safe water

to be supplied reliably and consistently, and this demand is growing.

As urban populations increase, there is a need

to find new sources to meet the growing demand. If groundwater is available

this can often be used with minimal treatment but any surface water source will

need to be treated to make it safe.

For towns and cities, the water supply is then

best provided by large mechanised water treatment plants

(Figure 5.1) that draw water from a large river or reservoir, using pumps.

(‘Mechanised’ means that machines, such as pumps

and compressors, are used). The treated water is then distributed by pipeline.

The size of the treatment plant required is

determined by the volume of water needed, which is calculated from the number

and type of users and other factors.

There are often seven steps (Figure 5.2) in

large-scale water treatment for urban municipal water supply (Abayneh,

2004).

Each of the steps will be described in turn in

this section. The water utility (the organisation that runs

the treatment plants and water distribution system) will ensure by regular

analysis of the water that it adheres to quality standards for safe water.

Figure 5.2 The seven steps often used

in the large-scale treatment of water.

To protect the main units of a treatment plant

and to aid in their efficient operation, it is necessary to use screens to

remove any large floating and suspended solids that are present in the inflow.

These materials include leaves, twigs, paper,

rags and other debris that could obstruct flow through the plant or damage

equipment. There are coarse and fine screens.

Coarse screens (Figure 5.3) are steel bars spaced

5–15 cm apart, which are employed to exclude large materials (such as logs and

fish) from entering the treatment plant, as these can damage the mechanical

equipment.

The screens are made of corrosion-resistant bars

and positioned at an angle of 60º to facilitate removal of the collected

material by mechanical raking.

Figure 5.3 A coarse screen.

Fine screens, which come after the coarse screens, keep out

material that can block pipework at the plant. They consist of steel bars which

are spaced 5–20 mm apart.

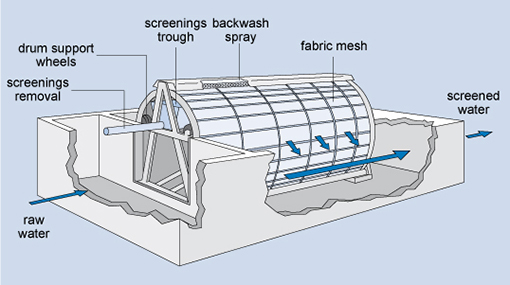

A variation of the fine screen is the microstrainer (Figure 5.4)

which consists of a rotating drum of stainless steel mesh with a very small

mesh size (ranging from 15 µm to 64 µm, i.e. 15–64 millionths of a metre).

Suspended matter as small as algae and plankton

(microscopic organisms that float with the current in water) can be trapped.

The trapped solids are dislodged from the fabric

by high-pressure water jets using clean water, and carried away for disposal.

Figure 5.4 Diagram of a

microstrainer.

After screening, the water is aerated (supplied

with air) by passing it over a series of steps so that it takes in oxygen from

the air.

This helps expel soluble gases such as carbon

dioxide and hydrogen sulphide (both of which are acidic, so this process makes

the water less corrosive) and also expels any gaseous organic compounds that

might give an undesirable taste to the water.

Aeration also removes iron or manganese by

oxidation of these substances to their insoluble form.

Iron and manganese can cause peculiar tastes and

can stain clothing. Once in their insoluble forms, these substances can be

removed by filtration.

In certain instances, excess algae in the raw

water can result in algal growth blocking the sand filter further down the

treatment process.

In such situations, chlorination is used in

place of, or in addition to, aeration to kill the algae, and this is

termed pre-chlorination.

This comes before the main stages in the

treatment of the water. (There is a chlorination step at the end of the

treatment process, which is normal in most water treatment plants).

The pre-chlorination also oxidises taste- and

odour-causing compounds.

After aeration, coagulation takes

place, to remove the fine particles (less than 1 µm in size) that are

suspended in the water.

In this process, a chemical called a coagulant (with

a positive electrical charge) is added to the water, and this neutralises the

negative electrical charge of the fine particles.

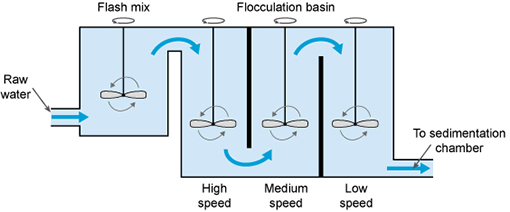

The addition of the coagulant takes place in a

rapid mix tank where the coagulant is rapidly dispersed by a high-speed

impeller (Figure 5.5).

Since their charges are now neutralised, the

fine particles come together, forming soft, fluffy particles called ‘flocs’.

(Before the coagulation stage, the particles all

have a similar electrical charge and repel each other, rather like the north or

south poles of two magnets.)

Two coagulants commonly used in the treatment of

water are aluminium sulphate and ferric chloride.

Figure 5.5 The

coagulation–flocculation process.

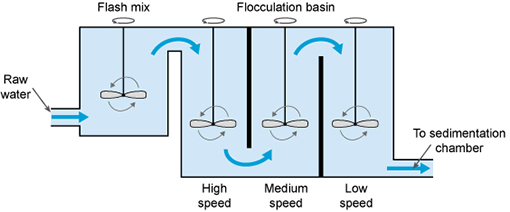

The next step is flocculation. Here

the water is gently stirred by paddles in a flocculation basin

(Figure 5.5) and the flocs come into contact with each other to form larger

flocs.

The flocculation basin often has a number of

compartments with decreasing mixing speeds as the water advances through the

basin (Figure 5.6(a)).

This compartmentalised chamber allows

increasingly large flocs to form without being broken apart by the mixing

blades.

Chemicals called flocculants can

be added to enhance the process. Organic polymers called polyelectrolytes can

be used as flocculants.

Once large flocs are formed, they need to be

settled out, and this takes place in a process called sedimentation (when

the particles fall to the floor of a settling tank).

The water (after coagulation and flocculation)

is kept in the tank (Figure 5.6(b)) for several hours for sedimentation to

take place. The material accumulated at the bottom of the tank is called

sludge; this is removed for disposal.

Figure 5.6 Flocculation chambers (a)

and a sedimentation tank (b) at Gondar water treatment works.

Filtration is the process where solids are separated

from a liquid. In water treatment, the solids that are not separated out in the

sedimentation tank are removed by passing the water through beds of sand and

gravel.

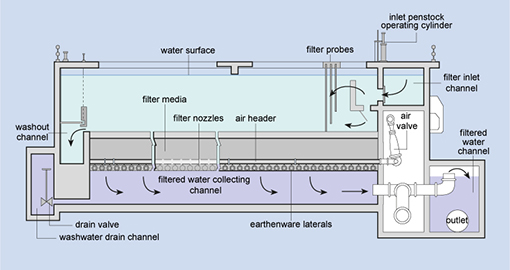

Rapid gravity filters (Figure 5.7), with a

flow rate of 4–8 cubic metres per square metre of filter surface per hour (this

is written as 4–8 m–3 m–2 h–1) are

often used.

When the filters are full of trapped solids,

they are backwashed.

In this process, clean water and air are pumped

backwards up the filter to dislodge the trapped impurities, and the water

carrying the dirt (referred to as backwash) is pumped into the

sewerage system, if there is one.

Alternatively, it may be discharged back into

the source river after a settlement stage in a sedimentation tank to remove

solids.

Figure 5.7 Cross-sectional diagram of

a rapid gravity sand filter.

After sedimentation, the water is disinfected to

eliminate any remaining pathogenic micro-organisms.

The most commonly used disinfectant (the

chemical used for disinfection) is chlorine, in the form of a liquid (such as

sodium hypochlorite, NaOCl) or a gas. It is relatively cheap, and simple to

use.

When chlorine is added to water it reacts with

any pollutants present, including micro-organisms, over a given period of time,

referred to as the contact time.

The amount of chlorine left after this is

called residual chlorine. This stays in the water all the way

through the distribution system, protecting it from any micro-organisms that

might enter it, until the water reaches the consumers.

World Health Organization Guidelines (WHO, 2003)

suggest a maximum residual chlorine of 5 mg l–1 of

water.

The minimum residual chlorine level should be 0.5 mg l–1 of

water after 30 minutes’ contact time (WHO, n.d.).

There are other ways of disinfecting water (e.g.

by using the gas ozone, or ultraviolet radiation) but these do not protect it

from microbial contamination after it has left the water treatment plant.

Following disinfection the treated water is

pumped into the distribution system.

Supplementary treatment may sometimes be needed

for the benefit of the population. One such instance is the fluoridation of

water, where fluoride is added to water.

It has been stated by the World Health

Organization that ‘fluoridation of water supplies, where possible, is the most

effective public health measure for the prevention of dental decay’ (WHO,

2001).

The optimum level of fluoride is said to be

around 1 mg per litre of water (1 mg l–1).

The safe level for fluoride is

1.5 mg l–1.

In such high-fluoride areas, removal or

reduction of fluoride (termed defluoridation) is essential.

The simplest way of doing this is to blend the

high-fluoride water with water that has no (or very little) fluoride so that

the final mixture is safe. If this is not possible, technical solutions may be

applied.

Two of these, the Nakuru Method and the Nalgonda

Technique, used in Ethiopia, are described below.

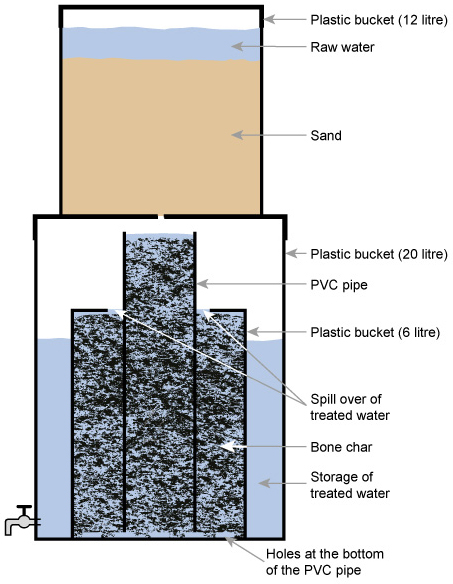

The Nakuru Method (Figure 5.8) involves a

filter with bone char (charcoal produced from animal bone) and calcium

phosphate to adsorb the fluoride (Kung, 2011).

There have been reservations on the use of bone

char, and alternatives for defluoridation, such as activated alumina, are being

tested in Addis Ababa (Alemseged, 2015).

Figure 5.8 The Nakuru method for

defluoridation using plastic buckets and piping.

The Nalgonda technique for defluoridation (Suneetha

et al., 2008) uses aluminium sulphate and calcium oxide to remove

fluoride.

The two chemicals are added to and rapidly mixed

with the fluoride-contaminated water and then the water is stirred gently.

Flocs of aluminium hydroxide form and these

remove the fluoride by adsorption and ion exchange. The flocs are then removed

by sedimentation.

Coarse screenings are usually sent to a landfill

or other waste disposal site. Fine screenings (in the form of a slurry) may be

discharged to a sewer, if there is one, or sent to a landfill.

The sludge from the sedimentation tank can be

sent to landfill, or to a sewage treatment plant. In the latter it is added to

the incoming sewage, where it can help settlement of solids.

The backwash from the sand filter is discharged

into the sewer or returned to the river after settlement of solids.

Packaging waste such as chemical drums can be

returned to the supplier for reuse. Wood and cardboard waste can be recycled.

In Study Session 4 you read about some factors

that can influence the sustainability of a water source. For example, reducing

soil erosion by planting trees and retaining vegetation can reduce the amount

of silt that accumulates in a reservoir and prolong its life.

For the water treatment process itself to

be sustainable (meaning that it can be maintained at its best

for a long time) it has to be simple to operate and maintain.

Complex systems should be avoided and wherever

possible locally available materials should be used. For example, if a

coagulant is required, the one that can be purchased in-country will be

preferable to one that has to be imported.

Water treatment plants consume energy, and if

this energy could be supplied through renewable sources (such as solar or wind)

it will keep operating costs down and improve sustainability.

The plant and distribution system should be made

of robust materials that will have a long operating life. It can be difficult

to obtain spare parts, so there should be plans in place for procurement of

replacements.

Another important factor in sustainability is an

effective maintenance system, which needs planning and, importantly, requires

well-trained and motivated staff.

Resilience, in the context of a water treatment system, is

its ability to withstand stress or a natural hazard without interruption of

performance or, if an interruption does occur, to restore operation rapidly.

With water treatment plants located very close

to water sources, having too much water can be just as much a problem for

operations as having too little.

Storms and floods, exacerbated by climate

change, may overwhelm systems and interrupt operations, so appropriate flood

defence measures must be in place.

The need to be resilient to these impacts is

another reason why the equipment and construction of the plant should be of a

high standard.

A critical factor in the sustainability of a

water supply system is ensuring that the volume of water provided is sufficient

to meet current and future demand.

Table 5.1 shows the water supply requirements

for towns of different sizes in Ethiopia according to the Growth and

Transformation Plan II.

Table 5.1- Water supply requirements for

urban areas in Ethiopia (note that for categories 1–4, the water should

be available at the premises). (MoWIE, 2015)

Urban category

|

Population

|

Minimum water quantity (litres per person per

day)

|

Maximum fetching distance (m)

|

1 Metropolitan

|

>1,000,000

|

100

|

–

|

2 Big city

|

100,000–1,000,000

|

80

|

–

|

3 Large town

|

50,000–100,000

|

60

|

–

|

4 Medium town

|

20,000–50,000

|

50

|

–

|

5 Small town

|

<20,000

|

40

|

250

|

The water needs of a town can be estimated from

the size of the population and the water requirements of users such as schools,

health facilities and other institutions within it.

The guidelines for the water supply requirement

of different categories of towns, shown in Table 5.1, may be used to

estimate the minimum quantity of water that should be supplied for a given

population.

There will be institutions in the town with

particular water requirements. Table 5.2 shows the requirements of some of

these in Ethiopia.

Table 5.2 Water requirements for

various types of institutions in Ethiopia. (Adapted from Kebeda and

Gobena, 2004)

Institution

|

Water requirement (litres per person per day)

|

Health centre

|

135

|

Hospital

|

340

|

Day school

|

18.5

|

Boarding school

|

135

|

Office

|

45

|

Restaurant

|

70

|

Once the consumers’ total water requirement has

been calculated, an allowance should be added for leakage losses, and for water

use by the water utility itself (for washing of tanks, etc.). This allowance

could, for example, be 15%.

The water will have to be stored in service

reservoirs. Service reservoirs have to hold a minimum of 36 hours’ or 1.5 days’

water supply.

Water provision for a small town

Imagine a town with a population of 5000 people,

and a health centre that treats 100 people a day.

The minimum water requirement per day for the

population (using the guidelines in Table 5.1) will be 40 litres x 5000 =

200,000 litres, or 200 m3.

The water requirement for the health centre

would be 135 litres x 100 = 13,500 litres, or 13.5 m3. The total

water requirement each day would be 200 + 13.5 = 213.5 m3.

Allowing for 15% leakage and water usage by the

water utility, each day the required volume of treated water supplied would be:

213.5 m3 x 1.15 = 245.5 m3.

This could be rounded up to 246 m3.

The service reservoir would need to hold a

minimum of 36 hours’ of supply (1.5 days). This means that the service

reservoir size would be:

46 m3 x 1.5 = 369 m3.

This could be rounded up to 370 m3.

The water requirement would therefore be 246 m3 per

day, and the minimum service reservoir capacity required would be 370 m3.

This volume could be held in one service

reservoir or shared between two, located in different parts of the town.

These simple calculations are included here to

give you an idea of the approach that would be taken to planning a new water

supply system.

In practice, the process would require many

different engineering, economic and environmental considerations involving a

team of experts.

The

Open University is a world leader in

the development of free Open Educational Resources (OER) as well as having

already taught over 1.8 million people worldwide. The OU is also the largest

academic institution in the UK with over 170,000 students currently enrolled on

its formal qualifications. OpenLearn can help get you started but you might

want to jump straight to The OU to see what qualifications you can start today!

|

Figure 5.8 The Nakuru method for defluoridation using plastic buckets and piping.

|

Figure 5.1 The water treatment plant

at Gondar, Ethiopia

|

|

Figure 5.2 The seven steps often used

in the large-scale treatment of water.

|

|

Figure 5.3 A coarse screen.

|

|

Figure 5.4 Diagram of a microstrainer.

|

|

Figure 5.5 The

coagulation–flocculation process.

|

|

Figure 5.6 Flocculation chambers (a)

and a sedimentation tank (b) at Gondar water treatment works.

|

|

Figure 5.7 Cross-sectional diagram of

a rapid gravity sand filter.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment