.............................................................................................................................................

.............................................................................................................................................

What's the Difference Between Pyrite and Gold?

BY MARK MANCINI

Martin Frobisher thought

he'd hit the jackpot.

The year 1576

found this English explorer and legal pirate — he was sanctioned by the crown

to plunder enemy treasure ships — seeking the Northwest Passage, the

undiscovered Arctic sea route that

links the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

He found something

else instead — Labrador, Canada, and what is now Frobisher Bay.

But weeks

later he sailed west and reached icy Baffin Island, where he

gathered a mineral sample that seemed to be flaked with gold. But it wasn't.

Not according

to the Royal Assayer who identified the shiny bits as pyrite, also known as

"fool's gold."

Undeterred,

Queen Elizabeth's merchants sent Frobisher back to Baffin, where he gathered

and shipped 1,400 tons (1,270 metric tons) of ore.

Most of it

was worthless;

in a few tested samples, the gold content was only five to 14 parts per

billion.

Though he

longed to abandon Baffin and go exploring again, Frobisher spent years

fruitlessly hunting Arctic treasure. And it was all because of that pyrite.

Elements and Compounds

Captain Christopher

Newport could likely sympathize.

As the leader

of Jamestown, England's first permanent settlement in North America, he was

constantly getting tricked by New World "gold" that turned out to be

— you guessed it — pyrite.

So, let's say

you're a prospector, or maybe just a bright-eyed field geologist. How do you

avoid pyrite's trickery?

Before we get

into that, it might be a good idea to explain what pyrite actually is in

the first place.

Real gold is

a chemical element,

a substance no ordinary chemical process — like electrolysis or heating — can

break down.

If you've got

a classroom periodic table handy,

look for gold between platinum and mercury.

Gold's

chemical symbol is "Au" (derived from the element's Latin-language

name, "aurum").

A fun way to

remember this is to say to yourself, "A! U! Give me back my gold!"

For maximum

entertainment value, use a Brooklyn accent.

Pyrite is

different. Unlike gold, it's a compound made up of two different elements: iron

and sulfur.

That's why

it's often referred to by the name "iron sulfide."

Scientists write

out pyrite's chemical formula as "FeS2."

You see, iron

and sulfur's chemical symbols are, "Fe" and "S,"

respectively. And each pyrite molecule contains one iron atom along with two

sulfur atoms.

Playing Rough

Telling gold

and pyrite apart really isn't that difficult if you know what you're doing.

Ever watch the

Olympics? Then you'll probably know those world-class athletes love to bite

their gold medals in

front of the cameras. (Seriously, it happens a lot.)

The practice

comes from the old belief that one can bite gold coins to see if they're

counterfeit.

Supposedly,

nibbling on any coin with a high gold content leaves bite marks behind.

The

truth's more complicated,

though, but the custom has a basis in fact.

On the Mohs' scale,

which rates the hardness of gems and minerals, gold has a ranking of 2.5 to 3. As elements go, it's

rather soft so a gold nugget can easily be scratched with a pocket knife.

Pyrite has the

advantage here; it's a bit harder and comes in at 6 to 6.5 on the Mohs' scale. Forget

knives; you'd need a high-quality metal file to

scratch this stuff.

Steel hammers

are another tool that can give the game away. Hit some pyrite with one of these

beauties and it'll send sparks flying.

If you're

persistent enough, the pyrite will shatter and eventually get reduced to a

powder.

None of that

happens when you strike gold with a hammer: No sparks, no powder.

Instead, you

might just end up expanding or

flattening the sample. Not only is gold soft, it's malleable to

boot.

See How I Glitter

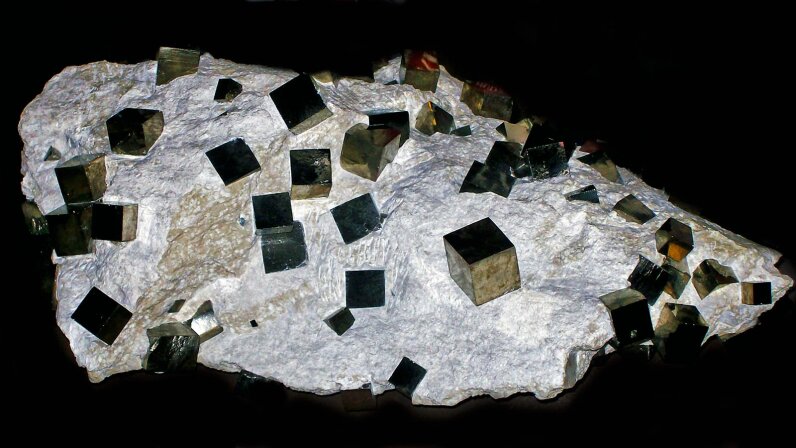

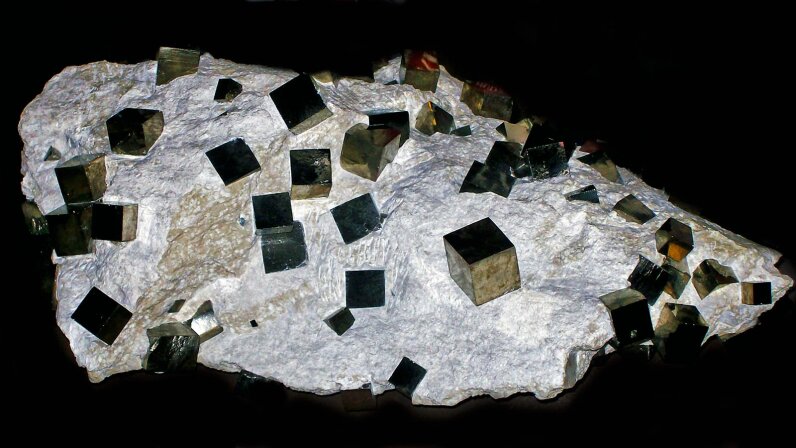

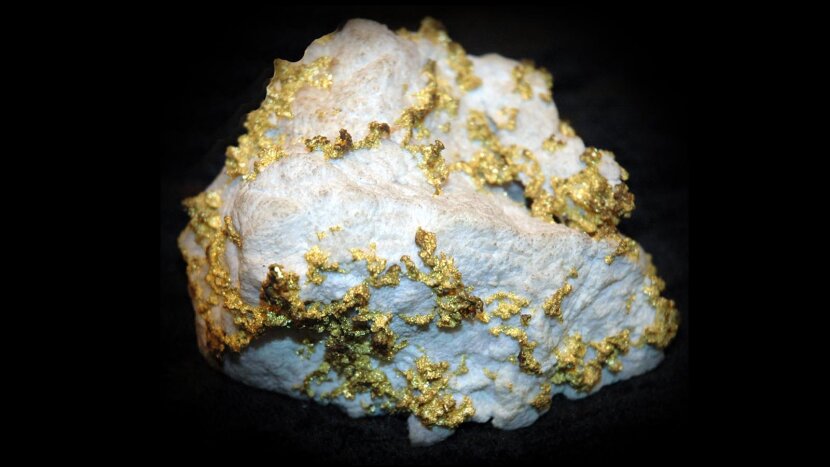

Visually, both

materials are yellowish, but gold is less brassy in hue. It also doesn't form

cube-shaped crystals, as pyrite often does.

On the

contrary, most of the gold encountered in the field takes the form of

either flakes or lumpy

nuggets.

Gold also will

leave a yellow streak behind if it's rubbed against a bit of porcelain or white

ceramic tile.

Repeat this

same experiment with pyrite and it will leave a darker, greenish-black line.

If you're

still in doubt, the nose knows. Although gold is pretty much odorless, pyrite

has a faint smell — and it smells like rotten eggs. (Again, it's loaded with

sulfur.)

But where

things can get confusing is gold and pyrite sometimes turn up in the same deposits.

Remember,

Frobisher's ore did contain some genuine gold — albeit a teeny, tiny amount.

If

"real" gold keeps eluding you, don't despair.

Fool's gold

isn't completely useless. Like we already mentioned, it can be used to produce

sparks, and thereby start

fires.

That made

pyrite a valuable commodity in ancient and prehistoric societies. Indeed, the

word "pyrite" itself came from a Greek term for "firestone."

Tomorrow may

bring a new appreciation for iron sulfide.

In 2020,

scientists at the University of Minnesota used electric voltage and an ionic

solution to successfully turn pyrite into a magnetic

material.

This

breakthrough could lead to low-cost, sulfur-based solar cells down the road —

giving fool's gold a bright future in the green energy industry.

NOW THAT'S INTERESTING

He never found

the Northwest Passage, but Martin Frobisher was knighted in 1588 for fighting

the Spanish Armada

Mark

Mancini

is a freelance writer currently based in New Jersey. Over the years, he’s

covered every subject from classic horror movies to Abe Lincoln's favorite

jokes. He is particularly fond of paleontology and has been reporting on new

developments in this field since 2013. When Mark's not at his writing desk, you

can usually find him on stage somewhere because he loves to get involved with

community theater. And if you ever feel like trading puns for a few hours, he's

your guy.

No comments:

Post a Comment